The Documentary

“To my mother and me, Grey Gardens is a breakthrough to something beautiful and precious called life.”

— Edie Beale, 1976

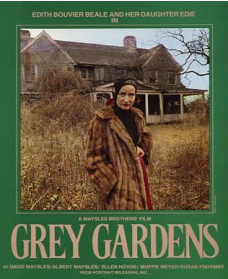

Filmed by Albert and David Maysles

- Directed by David Maysles, Albert Maysles, Ellen Hovde, Muffie Meyer

- Associate producer Susan Froemke

- Editors Ellen Hovde, Muffie Meyer, Susan Froemke

- Producer The Maysles Brothers, and Portrait Films, Inc

The International Documentary Association (IDA) ranks Grey Gardens as number nine among the top documentaries of all time. It has been honored at the Edinburgh, Cannes, and New York film festivals. A classic in the “direct cinema” genre, which brothers David and Albert Maysles pioneered through such films as Salesman (1968) and Gimme Shelter (1970), Grey Gardens is the story of “Big Edie” Bouvier Beale and her adult daughter “Little Edie” and the overgrown, crumbling East Hampton mansion they shared for decades with assorted cats, fleas, and raccoons. Direct cinema is a documentary film genre characterized initially by a desire to directly capture reality and represent it truthfully, and to question the relationship of reality with cinema. It is said to rely on an agreement among the filmmaker, subjects, and audience to act as if the presence of the camera does not (substantially) alter the recorded event.

The making of Grey Gardens actually came about by accident. Impressed with their work, the Maysles were approached by Lee Radziwill and her sister, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, about doing a documentary about their lives growing up in the Bouvier family. Their family, of course, included their eccentric aunt and cousin in East Hampton.

The brothers agreed to make the film; they shot footage over two weeks and immediately came to a startling realization: the charming and eccentric Beales would make much better film subjects than Jackie and Lee. As such, the Bouvier family documentary was quickly scrapped, much to the dismay of Lee. She, however, confiscated the initial footage of the Beales (reportedly over one and a half hours) and it has yet to see the light of day. There are rumors that she plans to release the footage sometime in the future.

The Maysles spent close to $50,000 on film and equipment before they went back to visit the Beales with their new proposal a year later. The women were ecstatic with the prospect of being filmed; it not only might offer them the fame that Jackie and Lee were accustom to, but would also give them the chance to make some much-needed money. The Maysles’ offer included an advance of $10,000 ($5,000 for Big Edie and $5,000 for Little Edie) and 20 percent of the future profits. With the green light, the Maysles, along with co-directors Ellen Hovde and Muffie Meyer, filmed the Beales for approximately six weeks in the fall of 1973. They practically lived at the mansion and resorted to wearing flea collars around their ankles to keep the bugs at bay.

The story the filmmakers recorded was like nothing ever seen before: the Beale-to-Beale mother-to-daughter dynamic was utterly incredible. It was both heartwarming and tragic, both bizarre and poignant all at the same time. An elderly mother, crippled with arthritis, and her 58-year-old unmarried daughter, live by the sea in a crumbling house filled with cats, faded pictures, filth and the cluttered memories of the their privileged past. The mother sings hits from the 1940’s like an opera star. The daughter marches and dances like a majorette. They bicker incessantly about missed opportunities and lost loves. They mainly survive on a diet of boiled corn (cooked on a bedside sterno), canned liver pate with crackers, and ice cream. They drink wine from a Dixie cup and enjoy the occasional Bacardi and Coke or can of light beer. They feed loaves of Wonder Bread and boxes of Cat Chow to the demanding raccoons that inhabit the attic.

The story the filmmakers recorded was like nothing ever seen before: the Beale-to-Beale mother-to-daughter dynamic was utterly incredible. It was both heartwarming and tragic, both bizarre and poignant all at the same time. An elderly mother, crippled with arthritis, and her 58-year-old unmarried daughter, live by the sea in a crumbling house filled with cats, faded pictures, filth and the cluttered memories of the their privileged past. The mother sings hits from the 1940’s like an opera star. The daughter marches and dances like a majorette. They bicker incessantly about missed opportunities and lost loves. They mainly survive on a diet of boiled corn (cooked on a bedside sterno), canned liver pate with crackers, and ice cream. They drink wine from a Dixie cup and enjoy the occasional Bacardi and Coke or can of light beer. They feed loaves of Wonder Bread and boxes of Cat Chow to the demanding raccoons that inhabit the attic.

They peer from the cracked windows suspiciously at curious passersby. Their witty dialogue, combined with an unusual dialect, was like something straight out of Tennessee Williams. And, the fashion, oh the fashion: swimsuits worn with high-heel pumps, a turban made from a sweater, a skirt worn upside down with fishnet stockings and a cape, and a sparkling brooch as the finishing touch added to every “costume.”

It took Hovde, Meyer, and Susan Froemke two years to edit the over 70 hours of film into a coherent story. The importance of the editors is obvious but often overlooked, as film editing can certainly make or break a film. The dynamic and creative roles of these three women are responsible for pulling together the complex elements of this unscripted slice of life. Any other collaboration of editors would have certainly produced an entirely different film.

The film debuted on September 21, 1975 in the upstairs hall of Grey Gardens; David, Al, Lois, Brooks, Little Edie, and Big Edie were there. They loved the film. Little Edie apparently remarked that she would be moving to Paris after the profits came rolling in. It was later showcased at the 1975 New York Film Festival. The movie made its public premier at the Paris Theater (located across from the Plaza Hotel) in Manhattan on February 20, 1976. It played there for just one week to mixed reviews from the New York Times and Village Voice. Audiences were both captivated and appalled at what they saw; many people viewed the Maysles as voyeurs and exploitive of the Beales. Little Edie even famously wrote a rebuttal letter to one critic that called the Beales a “circus sideshow.”

The film debuted on September 21, 1975 in the upstairs hall of Grey Gardens; David, Al, Lois, Brooks, Little Edie, and Big Edie were there. They loved the film. Little Edie apparently remarked that she would be moving to Paris after the profits came rolling in. It was later showcased at the 1975 New York Film Festival. The movie made its public premier at the Paris Theater (located across from the Plaza Hotel) in Manhattan on February 20, 1976. It played there for just one week to mixed reviews from the New York Times and Village Voice. Audiences were both captivated and appalled at what they saw; many people viewed the Maysles as voyeurs and exploitive of the Beales. Little Edie even famously wrote a rebuttal letter to one critic that called the Beales a “circus sideshow.”

It enjoyed limited box office success at the various art house theaters it played across the country. Even with the later release of VHS and DVD versions of the film (both stateside and abroad), Maysles Films says that Grey Gardens still has yet to make a profit (the Maysles financed the film completely themselves and it is estimated that it cost close to half a million dollars to make). Both Criterion and Masters of Cinema (current distributors of the DVD versions of the film) do not release current sales figures to the public, but admit that Grey Gardens is one of their most popular titles.

It enjoyed limited box office success at the various art house theaters it played across the country. Even with the later release of VHS and DVD versions of the film (both stateside and abroad), Maysles Films says that Grey Gardens still has yet to make a profit (the Maysles financed the film completely themselves and it is estimated that it cost close to half a million dollars to make). Both Criterion and Masters of Cinema (current distributors of the DVD versions of the film) do not release current sales figures to the public, but admit that Grey Gardens is one of their most popular titles.

According to Albert Maysles, when Edith Beale was dying, her daughter asked her if there was something more she wanted to say. “It’s all in the film,” Edith said.